Tags

Paul was on his way to Rome as a prisoner on a cargo ship, but a severe storm drove the ship way off course. The ship, with its crew, Roman guards and their prisoners, then drifted for days, eventually landing on a beach at a place called Mελíτη (Melita).

Acts 27:14-15, 27, 28:1 But the weather changed abruptly, and a wind of typhoon strength … burst across the island and blew us out to sea. The sailors couldn’t turn the ship into the wind, so they gave up and let it run before the gale … 27 About midnight on the fourteenth night of the storm, as we were being driven across the Sea of Adria, the sailors sensed land was near. … 28:1 Once we were safe on shore, we learned that we were on the island of Melita.

Where is Melita: Malta or Mljet?

Most Bible translations tell us Paul landed in Malta. It has been accepted since the Knights of St John moved their headquarters to Malta in 1530. The Vulgate (the Latin translation of the Bible) adopted this interpretation, and it’s still with us.

But the island of Mljet, near Dubrovnik in in the Adriatic Sea, was known as the Mileta of the Bible in seventh-century (Ananias of Shirak 600-650) and tenth-century records (Constanine Porphyrogenitus AD 905-959).

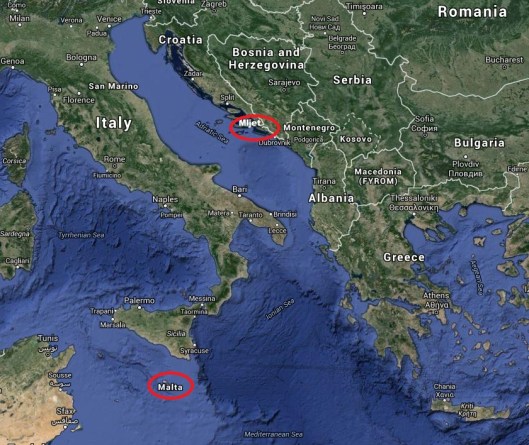

The two islands are shown in the map below.

Two islands named Melita: Mljet and Malta

Does it matter? malta or Mljet?

At one level, it doesn’t really matter. Who cares if someone flew from Sydney to Milan via Seoul or via Dubai? They still arrived and did whatever they had to do. On the other hand, the accuracy of historical details like this does matter to some people, and it affects their faith. This is for those people.

The case for MLJEt

Not everyone believed the Knights. A 16th-century Italian historian (Serafino Razzi, 1531-1611) reported a widespread view that Mljet was the real Mileta, as did several others during the next 100 years.

By 1730, the Benedictine monk, Ignjat Đurđević, decided to document both the oral and written tradition, and published St Paul the Apostle Castaway. A translation is available via: St Paul the Apostle spent three months on the island of Mljet in Croatia. (A translation of the original latin is at A study accompanying Croatian translation of the Đurđević’s book on Saint Paul’s shipwreck on the island of Mljet.

The basic arguments are:

- Melita was thought to be Mljet until the Knights rewrote history.

- Mljet is in the Sea of Adria, Malta isn’t (and it never was).

- The late autumn storms that sweep across that part of the world would usually blow a ship initially out to sea and then northwards into the Adriatic.

- Once the ship was disabled, the prevailing ocean currents would have caused it to drift northwards, up the Adriatic coast towards Mljet or a nearby island. It would be almost impossible to ave drifted to Malta from Crete.

- The sailors feared something called the Σύρτιν: these are more correctly translated as underwater rocks, rather than the sandbars of Syrtis (an improbable 400 or more miles away on the African coast).

- The description of the beach at Mileta more closely matches Mljet than it does Malta.

- There are snakes on Mljet (some have argued there are no snakes on Malta).

And it wasn’t just one Croatian historian who believed this. For example, an Englishman, Bryant Jacob, published a booklet in 1776, arguing along similar lines, but spending more time on the description of the wind (again to show the ship couldn’t have been blown towards Malta.) See Observations and inquiries relating to various parts of ancient history; containing dissertations on the wind Euroclydon …

Where does this leave us?

Paul was probably shipwrecked on Mljet in the Adriatic Sea, near modern-day Dubrovnik (a city I’ve always longed to visit, and now I have more reason to since it is the access point to Mljet).

Is the Bible wrong then? Well, no. While there are translation issues that spring from the power politics of the church in the 1500s, there is enough in the way of older Greek manuscripts of the Bible to easily get past it all.